The other day my wife and I are visiting my mother-in-law in Québec, and there is a show on TV about the origins of the Canadian flag. The more it goes on, the more I am engrossed in this rebranding drama. As a designer, I have a kinship with this story that differs from a Canadian citizen who loves their flag (a love that, I have been told, contains considerably less patriotic fervor than Americans’ passion for the stars and stripes). My relationship with this story stems from my passion for the specifics of the process and backstory of famous design projects, especially one of such national and international importance that it results in the creation of an iconic image and visual identity familiar to most people on the planet.

The other day my wife and I are visiting my mother-in-law in Québec, and there is a show on TV about the origins of the Canadian flag. The more it goes on, the more I am engrossed in this rebranding drama. As a designer, I have a kinship with this story that differs from a Canadian citizen who loves their flag (a love that, I have been told, contains considerably less patriotic fervor than Americans’ passion for the stars and stripes). My relationship with this story stems from my passion for the specifics of the process and backstory of famous design projects, especially one of such national and international importance that it results in the creation of an iconic image and visual identity familiar to most people on the planet.

A Peek at the Process

This insatiable desire to know the intimate details behind the creation of some of our most beloved brands’ marks is an irresistible design lust, an addiction. The ability to peek into the process—being allowed backstage to witness preliminary sketches, ideas that got trashed, creative briefs, positioning strategies and all the thought and the magic that transforms ideas into images is a delicious thrill. Polished and perfect logos reveal their very human origins. Seeing the evolution of a cultural institution—watching the familiar mark grow from a seed into its maturity—is to me, like witnessing the miracle of life unfold.

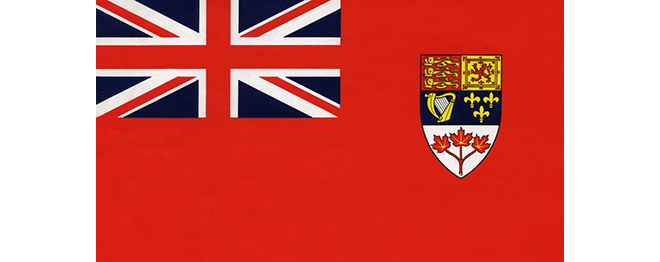

The Canadian “Red Ensign”, their previous flag, various versions of which had represented Canada since 1868

The Story of Rebranding a Nation

CTV ran the story “Seeking the origins of the Maple Leaf flag, finding the soul of our nation” in March 2014. It chronicles the entire process of a nation with an emerging identity, separate from England, that needs to rebrand. The old flag, the “Red Ensign” has served the country well, but the 1967 centennial celebration of Confederation was approaching, and there was a yearning for their own unique symbol. There were different groups within the decision-making body of politicians, with different agendas. Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson wanted a distinctive flag to promote national unity. Traditionalists and monarchists saw no need for change. A committee was sequestered into a secret room where the walls became covered with design ideas, some submitted by Canadian citizens from across the country. There were heated debates as competing ideas and interests were promoted.

Thousands of ideas, one final design

Eventually it came down to three finalists. I got goosebumps when I saw the sketch that became the final design, found on the back of a page in a committee member’s notebook. It’s the same way I still get excited over a looking at thumbnail sketches of any good design that ultimately makes its way into the public eye. An idea that was good enough to become real—that, when finished, successfully tells a story with line shape, color and form, evoking passion, transcending words.

The sketch that became the symbol of a nation. Discovered on the back of a page in a design committee member’s notebook.

How is this similar to our rebranding and marketing process today?

The process of defining a group of people, a company, or an idea, then designing, creating and developing an appropriate symbolic representation of them—whether it’s a 501(c)3 or a nation—is the same.

- The need for a new identity is usually a sign of growth and change.

- Creating a symbol and corporate identity requires consensus on values and mission, and a thorough, accurate knowledge of the brand and its positioning.

- There can be political considerations when different parties bring different, sometimes opposing criteria to the table.

- Sometimes resistance to change needs to be addressed. Why do we need a new identity? What was wrong with the old one?

- Working with qualified professionals is essential, not only for their design skills but for their objective, experienced counsel. (You may do this once or twice in a work lifetime; they’ve been there many, many times.)

- People will want to have input, show their own ideas, bring their spouse’s opinion(s) and/or cousin’s art to the design brief. Multiple ideas and collaboration are great, but design by committee can destroy a potentially strong identity.

- Ultimately a company leader must have the courage to make the decision on which design best represents the organization’s story and direction.

We rarely think of a country, state, county or other such designation as one in need of branding or rebranding. Fascinating, thank you.