As long as there are humans, there will be harmful vices; and as long as there are harmful vices, there are those who will profit from them. Of course, as long as there are people trying to profit from something, there are some marketers who will try to profit from those profiteers. And apart from the moral issue of whether or not it’s right to promote harmful products (which is a large moral issue, indeed), there’s the practical matter of exactly how you go about promoting things that are obviously bad. How do you sell bad?

I’m going to investigate what marketers for the tobacco industry have done to try to sell their death sticks, but to put the problem in its most absurd form, imagine you are tasked with selling something that’s not necessarily bad for you, but bad in some other aspect. For example, what if you had to sell a terrible tasting food item? Or a horribly ugly car? What benefit could you find in such a product to make people buy it? Leave it to the genius of marketing to come up with viable strategies.

So, the question that will guide us through the rest of this post is: As it became clear to the public that tobacco is harmful in a number of ways, how did the tobacco industry pursue the marketing of cigarettes during the heyday of tobacco advertisements in magazines (1930s through the 1970s)?

Lessened Harm as a Benefit

If you can’t claim any health benefits, you can point out something at which your product is not quite as harmful as the competition. People might, with proper sleight of hand, see this as a benefit instead of a lessened harm. Here was Camel’s take on this strategy, with their slogan: “Not one single case of throat irritation due to smoking Camels.”

(There’s a similar ad here: http://www.flickr.com/photos/clotho98/3969287963/.)

Just Smoke

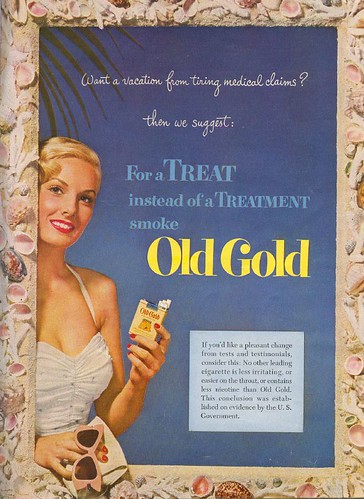

I suppose people weren’t buying the lessened-harm-as-a-benefit motif. So the reaction from marketers was to swing things back in the other direction. Don’t listen to these so-called health claims; just smoke, dammit! Old Gold cigarettes tried this tack with their “If you want a treat instead of a treatment…” campaign.

I imagine this must have been somewhat successful, especially with people who were tired of being lied to. But of course, there’s only so much traction this can gain, with the continued withering reports of ill-effects that cigarettes cause. (Here’s another similar one at Flickr.)

The Silver Lining

And so we enter into the strategy of trying to find actual health benefits from smoking. My favorite attempts at this are both from Camel. The first is something of a genuine attempt at digging up some benefit: “For digestion’s sake — smoke Camels”:

Camel’s other attempt at this is just plain comical: “It’s a psychological fact: Pleasure helps your disposition. For more pure pleasure, have a Camel.” Smoking makes you happy, which is good for you. Smoke away!

Fallacies

Another strategy was to try using fallacies in ads. Here’s a good one from Max cigarettes: “You can smoke fewer cigarettes by smoking longer ones. It’s wacky, but it works!”

The implicit message is of course that if you smoke fewer cigarettes, it’ll be better for your health. But of course this isn’t true if the cigarettes are bigger.

The Last Line of Defense

Sooner or later, tobacco marketers must have figured out that the addictive properties of their product are stronger than, well, just about anything. And there are two lines of strategy to stem from this realization. The first is essentially this: You’re really going to smoke, so be real about it; real people smoke, and you’re a real person. This spawned the Marlboro Man:

as well as other analogues, such as the Camel Man and the equally rugged Winston Man.

The second strategy is essentially this: You know you’re not going to quit, so why not some smoke something light that will be a little less harmful? True cigarettes latched onto this strategy with their slogan: “Considering all I’d heard, I decided to either quit or smoke True. I smoke True.”

To be honest, I’m not sure what lessons are to be taken from this brief exploration. The obvious moral of the story, I suppose, is for consumers: beware of marketers — they’re crafty and might be trying to sell you something bad. For us in the business, we can take this as a lesson in creativity. If you’re selling something bad, you’re going to need to get doubly creative — once to try to bamboozle the public, and once to come up with an interesting campaign.

Here at Marketing Partners, we’re glad to be social marketers — systematically applying commercial marketing techniques to achieve a social good. It leaves us a lot more time and energy to apply creativity to our work instead of devious strategizing.