We have several articles here about using other people’s content on your website, depending on what licenses they’ve used, but we haven’t touched on the idea of how you should go about licensing your own content for use on the web. In this post, I’ve gathered some resources regarding intellectual property licensing, as well as a little bit of history to put things in context.

Creative Commons Licenses

Creative Commons Licenses

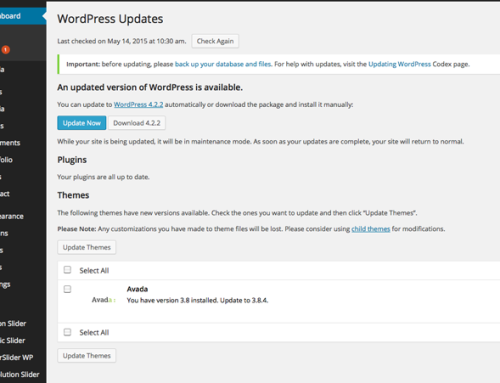

It seems that everywhere you go on the web, you see the phrase “Creative Commons” in one context or another. Creative Commons is a nonprofit corporation that has come up with a set of clear, effective licenses for public use on the web (and elsewhere). The Creative Commons system is simple and steps you through the process of thinking about how you want your work to be used by others. Do you want to allow commercial uses of your work? Do you want to allow other people to modify your work? Under what circumstances? It boils down to six basic licenses that you can apply to your works to properly protect them the way you see fit.

- Attribution — Lets others more or less do what they want with your work, even commercially, as long as they give you credit.

- Attribution Share Alike — As above, but others must license any derivative creations under the same terms.

- Attribution No Derivatives — Allows for redistribution, as long as your work is passed along unchanged and in whole, giving you credit.

- Attribution Non-Commercial — Lets others more or less do what they want with your work, but only non-commercially.

- Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike — As above, but others must credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms.

- Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives — Allows for redistribution, as long as your work is passed along unchanged and in whole, for non-commercial use, giving you credit.

These six licenses cover most of the cases for how one might want to license their works on the web. But just to give you a little history on how the Creative Commons licenses came to be, and so you have some further options for licensing your work, I present to you the mighty GPL.

The GPL

The motivation behind Creative Commons was in part a reaction to the original big player in public licenses: the Free Software Foundation and its influential GNU General Public License (GPL). The problem the GPL was invented to address was that of creating properly licensed “free” software. I put “free” in scare quotes because freedom here is not simply monetary; it is based upon the following necessary conditions: the freedom to use the software for any purpose; the freedom to change the software to suit your needs; the freedom to share the software with your friends and neighbors; and the freedom to share the changes you make.

It seems simple enough to license a work that you create such that anyone can use it, change it, and share it — in fact, you might be wondering why bother to license it at all? Just put it out there and let people run with it.

Ah, but then there are two problems. One is somewhat philosophical: In a world where everything was licensed freely, you wouldn’t have problems like unreasonably restrictive licenses on things you think you own, like CDs, MP3s, and DVDs. (You know that generally you just license these materials, right? You don’t own them.) But there are restrictive non-GPL licenses out there, and so the GPL is in part a mission-driven thing, trying to spread itself through the world and let freedom ring. The other problem — and of more practical importance — with just giving away your work without a license is this: how do you stop someone from taking your work, stripping your name from it, and using it for evil (i.e., in a way that restricts your freedoms)? The mission of the GPL, then, was this:

Developers who write software can release it under the terms of the GNU GPL. When they do, it will be free software and stay free software, no matter who changes or distributes the program. We call this copyleft: the software is copyrighted, but instead of using those rights to restrict users like proprietary software does, we use them to ensure that every user has freedom.

The GPL was created with the goal of being self-propagating. If you license your work under the GPL, then if your work is used by someone else in a derivative product, the GPL comes along with it for the ride, making the derivative product GPL licensed as well. Fans of the GPL think of this as helpful inheritance; detractors have gone so far as to say that the GPL “infects” everything it touches.

Choices, Choices, Choices

Creative Commons licenses don’t have the same overarching philosophical goals as the GPL, and they are therefore simpler and generally more applicable to things you might post for sharing on the web — images, videos, songs, blog posts, essays, and the like. However, if you are looking for a more complex license for your online work, you can check out the GPL as well as other similar licenses, such as the BSD Licenses, and the MIT License. The organization behind the GPL has a pretty comprehensive list of alternative licenses.

The world of licensing is complicated, but it’s important to make your way through the thicket. And, thanks to organizations like Creative Commons, making your way through it all is easier than it has ever been. Posting material on the web without doing your due diligence and protecting it in the way you see fit is just silly. Do some reading, and choose wisely! (And remember, licensing is not the same as copyrighting. Copyright protects your ownership rights to a creation; licensing allows you to dictate under what terms others can use your creation. For more information on copyrighting, check out the U.S. Copyright Office, and this article on European Union Copyright Law.)